- Home

- Penny Jordan

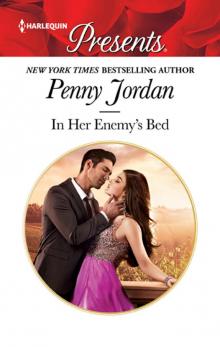

In Her Enemy's Bed Page 2

In Her Enemy's Bed Read online

Page 2

‘Your stepbrother, Jaime y Felipe des Hilvares—but you must call me Jaime.’ As he spoke he swung down from his horse, and from round the side of the building a gnarled, bow-legged man came hurrying to take the reins from him and lead the animal away.

Her new stepbrother said something to the groom in Portuguese, the language making his voice far softer and more liquid than it had appeared when he spoke to her. The groom’s face split in a wide smile, his head nodding. ‘Sim, Excelentíssimo… sim…’

Against her will Shelley suffered a sharp sense of shock. She had known of course about her stepbrother’s title, but such a blatant acknowledgement of it was not something she had anticipated.

He looked arrogant, she thought, studying him covertly and trying to quell her sense of suddenly having stepped on to very unfamiliar and alien ground. There was nothing in her background or her present life to equate with this. Contrarily, she decided she was not going to let that put her at a disadvantage. If her stepbrother chose to be supercilious and contemptuous towards her because he possessed a title and she did not, well, he would soon learn that she was not so easily cowed.

‘It is rather hot out here, Jaime,’ she said, ‘and I have had a long drive…’

‘Indeed…and yet you look remarkably cool and fresh.’

He was looking at her assessingly, hard grey eyes studying her slender form in its covering of white top and jeans.

‘We are very honoured that you have at last chosen to visit us, and you do right to remind me that I am being less than courteous in keeping you standing here in our hot sun. Please follow me.’

Again his voice was tinged with sarcasm, his mouth hardening imperceptibly as he moved towards her, his whole manner towards her somehow suggesting that he was holding himself tightly in control, and that beneath that cool polite surface simmered a dislike he was only just holding in check.

But why should he dislike her?

He moved, the sunlight shining sharply across his face, revealing for the first time the high cheekbones and harshly carved features that were another legacy of the Moors’ occupation of the Algarve. His skin was tanned a warm gold, making her all too aware of her own pallor. Her skin was very pale and only coloured very slowly. She felt positively anaemic standing at the side of this dark-haired, golden-skinned man. She also felt almost frighteningly small and fragile. She had not expected him to be so tall, easily six foot with the broad shoulders and muscled body of an experienced rider. As he walked towards the door, Shelley saw that he moved with a coordinated litheness that was curiously pleasing to the eye.

‘I thought you wanted to go inside because you were too hot?’ He was watching her she saw, his expression politely aloof, but his mouth gave him away. It was curled in open, contemptuous dislike. The shock of that dislike drove away her embarrassment at being caught scrutinising him.

His aloofness she could have accepted, even approved of; after all, it was her own response to strangers and acquaintances. But his contempt! The contempt of her peers was something she had never had to deal with. On the contrary, she was aware that most people who knew her held her faintly in awe and accorded her their respect. In her work she had occasionally come across men who affected to despise the female species in its entirety, but her crisp no-nonsense manner soon convinced them that she was not going to be influenced by such anti-female tactics. And anyway, Jaime was not anti-women, not trying to prove some superior male psychology. It was her he despised. She had seen that plainly enough in his eyes. But why?

Warily she followed him into the cool tiled hall. The shutters had been closed to keep out the strong heat of the sun and, momentarily blinded, she missed her step and grabbed instinctively at his arm.

Beneath his shirt sleeve his muscle were hard and rigid, his flesh warm and dry. Her fingertips seemed acutely sensitive all of a sudden, relaying to her his abhorrence of her touch. Even so, he courteously helped her regain her balance.

Perhaps it was the way she looked that he didn’t like, Shelley pondered as her eyes adjusted to the dim light. Perhaps… Abruptly she curtailed her thoughts. What did it matter why he didn’t like her? She had come here for one purpose, and that was to discover the father she had never known she had. Her inheritance from him, whatever it might be, was of secondary and very little importance. She had no assets in the sense that her stepbrother would consider such matters, but she had a well-paid job and had supported herself virtually from the moment she went to Oxford. She liked and felt proud of her financial independence, and whatever her father left would be cherished because he had been the donor, because he had after all cared about her and loved her, rather than for its monetary value.

Several doors gave off the hallway. As he showed her into one of them, Jaime explained that the main part of the house was built round an open courtyard and that most of the rooms overlooked this cool oasis.

‘Through the years more rooms and smaller courtyards have been built on to suit the family’s needs. In Portugal it is the custom for several generations to share a home. This house passed to me from my father when I attained my majority, but naturally my mother and sister make their home with me.’

‘And my father…’

There was a small pause and then he said coolly,

‘He too lived here sometimes, although he had preferred his own house, which is on the coast.’

The note of restraint in his voice made Shelley frown. ‘This house…’

‘I appreciate how anxious you are to discover your father’s financial standing, Miss Howard,’ Jaime broke in harshly, making it plain that although he had given her permission to use his first name he preferred to maintain a cool distance between them by not using hers. ‘But these matters are best discussed with the advogado in Lisbon. I have arranged that he will call here tomorrow to discuss with you all the matters appertaining your father’s will—and now, if you will excuse me, I will get one of the maids to show you to your room. She will bring you some refreshment. We dine earlier here than in Spain, normally about eight in the evening. Again, Luisa will tell you.’

Already he was turning away from her, and incredibly, Shelley realised he intended to walk out and leave her.

Anger battled with trepidation. It was galling to discover how little she wanted to be left alone in this alien environment, no matter how attractive it might be, and no matter how unwelcoming her host.

‘Your mother and sister…’

‘They are out shopping at the moment, but will return in time for dinner.’

He saw her face and smiled cruelly. ‘What is wrong? Surely you cannot have expected to be greeted with a fatted calf? I must say that I admire your…courage, Miss Howard. It is not every child who would only condescend to visit the home of its father in such a blatant quest for financial gain. When I think of his attempts to contact you…his grief…’ He swallowed hard, and over and above her shock at his obvious misconception of her motives, once again Shelley had the impression of intense anger being held tautly in control. ‘No, you are not welcome in my home,’ he continued, ‘and nor shall I pretend that you are. For the love and respect I had for your father I am willing to see that his wishes are carried out. My mother is not here to greet you because she is still suffering desperately from her loss. Your father was the most important person in her life. Why didn’t you come before…while he was still alive? Or was it your inheritance that drew you here and not the man?’

He threw the question at her harshly, but she was too shocked to formulate an answer. Turning on his heel, he left the room abruptly.

Standing in the shadows, Shelley shivered. So now she knew the reason for his contempt. He thought… She took a deep, steadying breath, wondering if she could call him back and tell him the truth, but somehow it seemed to be too much effort. Incredibly, she felt as weak and shaky as though she had just gone through an intense physical and emotional ordeal. She felt almost bruised both inwardly and outwardly.

She wo

uld have given anything to drive away from the quinta and never return, but she owed it to her father’s memory to stay. Seen from her stepbrother’s viewpoint, perhaps he and his family had good reason to think the way they did, but surely they might have given her the benefit of the doubt; might have waited, and not pre-judged. The stubborn pride she had inherited from her grandmother urged her to leave now and ignore her father’s bequest, but she had come too far, gone through too much to leave now without accomplishing her mission.

She had come to Portugal with a purpose, and that purpose was to learn about the father that she had not known she had until recently; she was not going to allow her arrogant, judgemental stepbrother or his family to stop her. They could think what they liked of her, but she intended to make it clear to them that it wasn’t avarice that had brought her to their home, unless a desire to learn about the man who had been her father could be classified as a form of greed.

So silently that she almost made her jump, a young girl came into the room.

‘I am Luisa,’ she informed Shelley with a charming accent. ‘I show you to your room, sim… Yes?’

‘Yes, please.’

CHAPTER TWO

BY accident rather than design, Shelley didn’t make it to the dinner table at eight o’clock. Instead, it was gone ten when she finally surfaced from a deep but unrestful sleep. The brief span of time it took for her to recognise her surroundings was accompanied by a downward lurch of her stomach and a sense of growing despondency.

She had come to Portugal with such high hopes, and foolishly romantic ones, she realised now, ruthlessly exposing to her own self-criticism the folly of her ridiculous longings for a family of her own—the sort of family that comprised brothers and sisters, aunts, uncles and cousins, the sort of family she had heard colleagues bemoan times without number, the sort of family, she had told herself staunchly when her grandmother died, that she did not need.

Dreams took a long time to die, she recognised emptily, but last night hers finally had. She was not welcome here in Portugal. Even once the misconceptions surrounding her reasons for coming to Portugal were sorted out, she would still not be welcome. Her pride demanded that she didn’t leave the quinta until she had made it plain to Jaime exactly why she had come, but her pride also demanded that no matter what apology he might make, no matter how he might seek to make amends for misjudging her, she would hold him at a distance.

He wasn’t what she had wanted in a stepbrother anyway. It was impossible for her to ever envisage him in a brotherly role. That overwhelming aura of sexual magnetism of his would always be something she was far too much aware of. She shivered a little, goosebumps forming on her flesh as she remembered the contemptuous way he had looked at her.

Outside her open window she could hear the sound of crickets, the warm air stirring the curtains, reminding her that she was now in a foreign country.

She felt thirsty, and far too keyed up to go back to sleep. Her cases were neatly stacked on a long, low chest; someone had emptied them while she slept. Opening the wardrobe, she took out a slim-fitting cotton dress.

She managed to find her way to the top of the stairs without difficulty, but once down in the hall was totally confused as to the whereabouts of the kitchen. Her throat, which had felt merely slightly dry when she first woke up, now felt like sandpaper and, calculating back how long it had been since she had last had a drink, she suspected she might be suffering slightly from dehydration.

She felt more vulnerable and unsure of herself than she could remember feeling for a long time. The years in foster homes had taught her well how to guard herself against the hurts unwittingly inflicted by others. It had been a long time since anyone had been allowed to hurt her, and even longer since she had cried, but today she had come perilously close to experiencing both.

The sharp sound of a door opening made her jump, her face setting in lines of cold rejection as she saw her host striding towards her.

‘So, you have decided to grace us with your presence after all. A pity you did not deign to join us for dinner.’

The insolent contempt in his voice banished all her good intentions not to let him provoke her into further hostilities. Acting with an impulsiveness that later would shock her, Shelley responded curtly. ‘Why should I? You obviously know exactly what I’m here for, so, as you’ve already made abundantly plain, there is scarcely any need for the normal civilities between us.’

She saw that something in her cold words had caught him on a sensitive spot. A wave of dark colour—probably anger rather than embarrassment—stained the tanned skin, his eyes glittering with suppressed rage. She had once read somewhere that these Moorish Portuguese were a very proud and correct race, and she judged that he would not appreciate her criticism of his reception of her.

Spurred on by her success, she added dulcetly, ‘You’re obviously a very clever man, Jaime, to be able to analyse so correctly and assess the reactions of others without meeting or knowing them.’

This time he had himself well under control, only his voice faintly clipped and harsh as he responded, ‘You flatter me, I’m afraid. In your case very little intelligence was needed; one merely had to look at the facts. A daughter who refuses to make herself known to her father until after his death, when almost miraculously she suddenly appears on learning that he had left her something of value; who would not even have given herself the trouble of coming out here at all if I hadn’t insisted that she did. Why did you never make any attempt to trace your father? While you were a child I can see that you must have felt bound by your grandmother’s desire not to see him, but once she had died—and I understand from the enquiries instituted by the lawyers that she died when you were fourteen—surely then you must have felt some curiosity about your father, some desire to find him?’

Her heart was pounding so heavily she could hardly breathe. It was plain to Shelley that Jaime had no idea to the real truth: that her grandmother had brought her up in the belief that her father was dead. But the same stubborn pride that had helped her endure so much as a child now refused to allow her to ask this man for his understanding or pity.

Instead of telling him the truth, she said curtly, ‘Must I?’

The absolute contempt in his eyes fuelled her anger, pushing her through the barrier of logic and caution to the point where she heard herself saying huskily, in a voice vibrating with emotion, ‘And by what absolute right do you dare to criticise me? You know nothing, either about me or about my motives in coming here. You are unbelievable, do you know that? You have the arrogance to criticise and condemn me without even trying to discover the facts; without knowing the first thing about me!’ Her eyes flashed huge and dark in her too-pale face, the violence of her emotions draining her last reserves of energy. She was literally shaking with the force of them, knowing that she was no match either physically or emotionally for this man, but driven to defy him.

‘I’m not staying here another minute!’ her voice rising now, her strength rushing away from her. ‘I’m leaving—right now.’

She turned sharply on her heel, her thirst forgotten, her one desire to leave the quinta just as soon as she could, but her flight was arrested by the hard fingers gripping her arm.

‘Be still!’

The rough shake that accompanied the hissed words almost rattled her teeth. She turned to look at him with loathing, shocked into immobility as the door he had come through suddenly opened and a woman stood there.

‘Jaime, querido, what is going on?’

She spoke in English, but even without that, Shelley would have know that this fair-haired woman could not be Portuguese.

So this was her father’s wife…her stepmother. As she looked into the delicately boned, fragile face, Shelley recognised the grief and pain in it. Yes, this woman had loved her father. A lump of cold ice formed round her own heart, the pain she had suffered as a child gripping her in a death hold as she met the worried blue eyes that looked first at her and the

n at Jaime.

‘Miss Howard seems to want to leave us,’ Jaime told his mother curtly. ‘I am just about to impress upon her the inadvisability of such a course of action. For one thing the village has no guest house or hotel, and for another, the advogado arrives tomorrow morning to discuss with her those matters relating to her father’s estate which concern her.’

Now, for the first time, her stepmother was forced to look at her. Up until now she had been avoiding doing so, Shelley recognised bleakly.

‘So you are Philip’s daughter. Your father…’ Tears welled in her eyes and she turned her head away. Jaime released Shelley’s arm to go to his mother’s side, his obvious care and concern for her so much in contrast to the way he had spoken to and touched Shelley that she felt her resentment and misery increase.

Part of her longed to burst out that it wasn’t fair, that she hadn’t been responsible for the split with her father, that she had suffered too, but caution and pain tied her tongue. She was not going to reveal her vulnerability in front of this man. He would enjoy seeing her pain… Oh, he would cloak his enjoyment with a polite semblance of concern, but deep down inside he would enjoy it.

The door opened again and a young girl came out. In her stepsister the Portuguese strain was less obvious than it was in Jaime, but she had her brother’s dark hair and olive skin.

Jaime said something to her in Portuguese, and after flicking a brief glance at Shelley she gently led her mother away.

‘I strongly advise you against leaving here tonight,’ Jaime told her coldly when his mother and sister had gone. ‘Of course, if you insist then I cannot stop you, but as I mentioned earlier, the advogado arrives tomorrow morning; there will be much he will want to discuss with you.’

‘And a great deal I shall want to discuss with him,’ Shelley told him fiercely. ‘Very well, Excelentíssimo.’ She let the title roll off her tongue with bitter sarcasm. ‘I shall stay until I have seen him, but believe me, your hospitality is as unwelcomely accepted by me as it is given by you.’

Woman To Wed?

Woman To Wed? Wanting

Wanting The Trusting Game (Presents Plus)

The Trusting Game (Presents Plus) Too Wise To Wed?

Too Wise To Wed? Time for Trust

Time for Trust Out 0f The Night (HQR Presents)

Out 0f The Night (HQR Presents) Dangerous Interloper (Lessons Learned II Book 8; HQR Presents Classic)

Dangerous Interloper (Lessons Learned II Book 8; HQR Presents Classic) Best Man To Wed?

Best Man To Wed? They're Wed Again

They're Wed Again Out of the Night

Out of the Night An Innocent's Surrender

An Innocent's Surrender Marriage: To Claim His Twins

Marriage: To Claim His Twins Deal With the Devil--3 Book Box Set

Deal With the Devil--3 Book Box Set Matter of Trust

Matter of Trust Vacation with a Commanding Stranger

Vacation with a Commanding Stranger A Savage Adoration

A Savage Adoration The Mistress Purchase

The Mistress Purchase Reclaimed by the Ruthless Tycoon

Reclaimed by the Ruthless Tycoon The Tycoon's Forbidden Temptation

The Tycoon's Forbidden Temptation Sinful Nights: The Six-Month MarriageInjured InnocentLoving

Sinful Nights: The Six-Month MarriageInjured InnocentLoving Bedding His Virgin Mistress

Bedding His Virgin Mistress Escape from Desire

Escape from Desire Claiming His Shock Heir

Claiming His Shock Heir Stronger than Yearning

Stronger than Yearning Return of the Forbidden Tycoon

Return of the Forbidden Tycoon Mission: Make-Over

Mission: Make-Over The Garnett Marriage Pact

The Garnett Marriage Pact Wanting His Child

Wanting His Child A Little Seduction Omnibus

A Little Seduction Omnibus The City-Girl Bride

The City-Girl Bride Craving Her Boss's Touch

Craving Her Boss's Touch Starting Over

Starting Over Phantom Marriage

Phantom Marriage The Italian Duke's Virgin Mistress

The Italian Duke's Virgin Mistress One Night in His Arms

One Night in His Arms Force of Feeling

Force of Feeling Forbidden Loving

Forbidden Loving For Better for Worse

For Better for Worse Silver

Silver Rival Attractions & Innocent Secretary...Accidentally Pregnant

Rival Attractions & Innocent Secretary...Accidentally Pregnant A Bride for His Majesty s Pleasure

A Bride for His Majesty s Pleasure Desire's Captive

Desire's Captive Forgotten Passion

Forgotten Passion Taken Over

Taken Over Taken by the Sheikh

Taken by the Sheikh Sicilian Nights Omnibus

Sicilian Nights Omnibus Darker Side Of Desire

Darker Side Of Desire A Royal Bride at the Sheikh s Command

A Royal Bride at the Sheikh s Command The Ultimate Surrender

The Ultimate Surrender A Reason for Being

A Reason for Being A Cure for Love

A Cure for Love Bought with His Name & the Sicilian's Bought Bride

Bought with His Name & the Sicilian's Bought Bride Marriage Make-Up & an Heir to Bind Them

Marriage Make-Up & an Heir to Bind Them Bitter Betrayal

Bitter Betrayal Captive At The Sicilian Billionaire’s Command

Captive At The Sicilian Billionaire’s Command Valentine's Night

Valentine's Night The Convenient Lorimer Wife

The Convenient Lorimer Wife Reawakened by His Touch

Reawakened by His Touch Substitute Lover

Substitute Lover Passionate Protection

Passionate Protection The Hidden Years

The Hidden Years So Close and No Closer

So Close and No Closer Passion and the Prince

Passion and the Prince Virgin for the Billionaire's Taking

Virgin for the Billionaire's Taking Cruel Legacy

Cruel Legacy Payment in Love

Payment in Love The Wealthy Greek's Contract Wife

The Wealthy Greek's Contract Wife Penny Jordan Collection: Just One Night

Penny Jordan Collection: Just One Night Permission to Love

Permission to Love Beyond Compare

Beyond Compare When the Magnate Meets His Match

When the Magnate Meets His Match A Time to Dream

A Time to Dream Christmas Nights

Christmas Nights Christmas with Her Billionaire Boss

Christmas with Her Billionaire Boss The Sheikh's Baby Omnibus

The Sheikh's Baby Omnibus The Tycoon's Virgin

The Tycoon's Virgin Falcon's Prey

Falcon's Prey Mistress Of Convenience

Mistress Of Convenience The Perfect Father

The Perfect Father Stranger from the Past & Proof of Their Sin

Stranger from the Past & Proof of Their Sin A Little Revenge Omnibus

A Little Revenge Omnibus Loving

Loving Lesson to Learn

Lesson to Learn Second Chance with the Millionaire

Second Chance with the Millionaire Payment Due

Payment Due A Secret Disgrace

A Secret Disgrace Conveniently His Omnibus

Conveniently His Omnibus An Unforgettable Man

An Unforgettable Man The Tycoon She Shouldn't Crave

The Tycoon She Shouldn't Crave Pride & Consequence Omnibus

Pride & Consequence Omnibus The Dutiful Wife

The Dutiful Wife Bought With His Name

Bought With His Name The Friendship Barrier

The Friendship Barrier High Society

High Society The Price of Royal Duty

The Price of Royal Duty A Scandalous Inheritance

A Scandalous Inheritance At His Convenience Bundle

At His Convenience Bundle The Blackmail Baby

The Blackmail Baby Prince of the Desert

Prince of the Desert A Sudden Engagement & the Sicilian's Surprise Wife

A Sudden Engagement & the Sicilian's Surprise Wife Unexpected Pleasures

Unexpected Pleasures Levelling the Score

Levelling the Score Savage Atonement

Savage Atonement Dangerous Interloper

Dangerous Interloper A Passionate Awakening

A Passionate Awakening Ruthless Passion

Ruthless Passion Time Fuse

Time Fuse Past Passion

Past Passion Her One and Only

Her One and Only The Innocent's Secret Temptation

The Innocent's Secret Temptation A Stormy Spanish Summer

A Stormy Spanish Summer The Marriage Demand

The Marriage Demand Future King's Pregnant Mistress

Future King's Pregnant Mistress Unwanted Wedding

Unwanted Wedding Giselle's Choice

Giselle's Choice Now or Never

Now or Never Blackmailed by the Vengeful Tycoon

Blackmailed by the Vengeful Tycoon Lovers Touch

Lovers Touch Scandalous Seductions

Scandalous Seductions The Power of Vasilii

The Power of Vasilii Possessed by the Sheikh

Possessed by the Sheikh It Happened At Christmas (Anthology)

It Happened At Christmas (Anthology) The Perfect Lover

The Perfect Lover The Flawed Marriage

The Flawed Marriage The Greek's Runaway Bride

The Greek's Runaway Bride An Unbroken Marriage

An Unbroken Marriage Hired by the Playboy

Hired by the Playboy The Blackmail Marriage

The Blackmail Marriage Daughter of Hassan

Daughter of Hassan Campaign For Loving

Campaign For Loving The Boss's Marriage Arrangement

The Boss's Marriage Arrangement Seduced by the Powerful Boss

Seduced by the Powerful Boss Marriage Without Love & More Than a Convenient Marriage?

Marriage Without Love & More Than a Convenient Marriage? Bride in Name Only

Bride in Name Only Her Shock Pregnancy Secret

Her Shock Pregnancy Secret Propositioned in Paradise

Propositioned in Paradise The Only One

The Only One The Sicilian s Baby Bargain

The Sicilian s Baby Bargain The Trusting Game

The Trusting Game The Most Coveted Prize

The Most Coveted Prize One-Click Buy: September Harlequin Presents

One-Click Buy: September Harlequin Presents In Her Enemy's Bed

In Her Enemy's Bed An Expert Teacher

An Expert Teacher A Rekindled Passion

A Rekindled Passion The Reluctant Surrender

The Reluctant Surrender Shadow Marriage

Shadow Marriage A Scandalous Innocent

A Scandalous Innocent Forbidden Kisses with the Boss

Forbidden Kisses with the Boss Bound Together by a Baby

Bound Together by a Baby Second-Best Husband

Second-Best Husband Response

Response His Untouched Bride

His Untouched Bride A Kind of Madness

A Kind of Madness Past Loving

Past Loving His Blackmail Marriage Bargain

His Blackmail Marriage Bargain For One Night

For One Night Legally His Omnibus

Legally His Omnibus Back in the Marriage Bed

Back in the Marriage Bed Man-Hater

Man-Hater